I work for a small company that specializes in digital signage, on-hold messaging, and overhead music. I have my hands in everything, front to back.

Years ago, I wrote the code that constitutes the on hold and overhead music in C#, which has been an absolute pain to deal with since these players are on-site all across the country. (Thousands of them) There is just no way for a small shop to keep up with Microsoft’s dotnet release pace anymore.

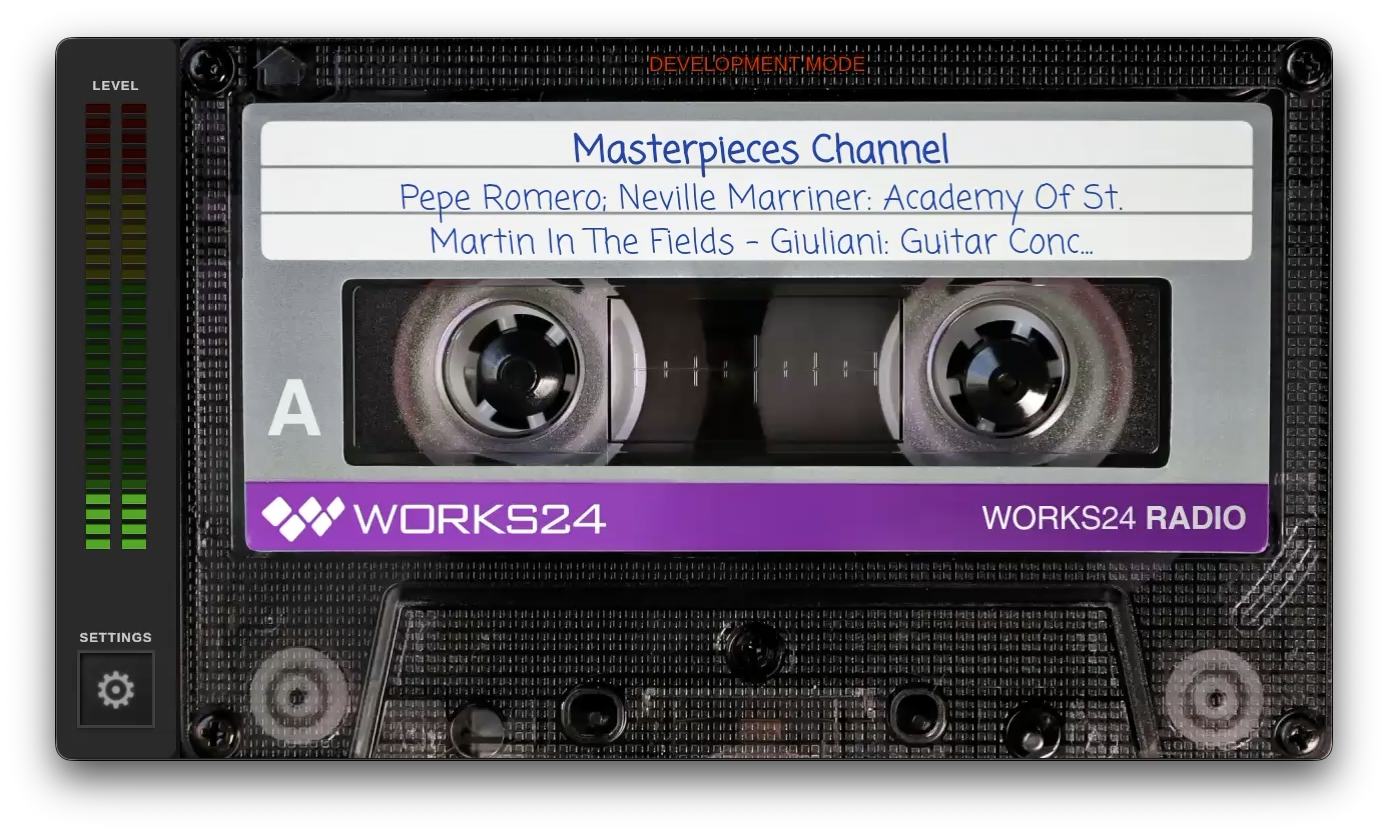

So I decided I’d like to simplify my programming life a bit and learn Go, then port my C# project to Go as a capstone of sorts. Even though I know better than to add more than one new technology to any project, I decided to break my rule and also mix in AI… Oh, and also Wails for the UI. How hard could all of this be?

You can probably guess how accurate my estimate ended up being for this project.

The first thing to point out is just how much AI coding agents have progressed in the last 6-8 months. I started with Qwen coder, then moved to JetBrains original AI agent (Did it have a name?) then to Junie, then finally to Claude Code. Junie was where I really started to see the potential of agents. With Qwen I had to have it convert one file at a time, starting with the files at the end of the dependency chain and working (slowly) back up to the main file. If I told it to convert the whole codebase, it would go into Roomba mode, hoover up everything in sight, run out of context then start a downward spiral into madness. Thank god for git.

I’m the type of guy who likes to know where he’s going BEFORE he gets in the car. I know, I know, I should be more agile. You can imagine how happy I was once I discovered Claude could handle huge amounts of context and I could explain the whole summer vacation itinerary to it.

The more I explained what I was trying to accomplish and how I wanted to get there, the better Claude did. Imagine that.

Planning mode is a stroke of genius. I have spent 30 minutes or more explaining to Claude how I wanted a feature implemented, Claude would create a plan, I would pick it apart, Claude would provide a rebuttal, back and forth we’d go. The more we collaborated (argued?) the higher the likelihood Claude would nail the feature on the first try. It’s getting harder and harder to not assign the “he” pronoun to Claude. I name my cars, so I’m not sure why I’m hesitant to personify Claude.

To put this in context, the LOC of the project is about 12k lines, nothing back breaking for sure. But there is significant complexity in modifying existing code with new features that require modifying dozens of individual files. Understanding the abstractions, dependencies, and even the style of the existing code, then modifying it and getting it all right the first time is pretty damn impressive. Claude managed that feat a few times there near the end of the project.

I’m not sure who is training who at this point.